Bond Allocation#

It is commonly preached that bonds are essential to a sustainable portfolio. But how true really is this statement? After all, bonds are commonly known to sacrifice performance, so to have a portfolio with the lowest amount necessary is optimal.

To explore the effects of bonds, we will compare 5 different stock/bond allocations; a control 100% stock allocation, along with the 4 different allocations based approximately on the Vanguard ready-made portfolios.[1]

| Fund | Stock/Bond Allocation |

|---|---|

| Control | 100 / 0 |

| VDHG (High Growth) | 90 / 10 |

| VDGR (Growth) | 70 / 30 |

| VDBA (Balanced) | 50 / 50 |

| VDCO (Conservative) | 30 / 70 |

Methodology#

The most basic way to observe whether one allocation is better than the other is to look at the mean and standard deviation of performance over time. However, this approach is too abstract for my tastes, and misses a lot of nuance. Here I’ll explain my approach.

First we need to define what a retirement fund is. A retirement fund is an investment portfolio where a regular living expense can be withdrawn perpetually. This is possible in theory when the amount gained from your portfolio performance is greater than the amount you withdraw each year. It is commonly advised that an investment portfolio worth 25x your annual living expenses is the lowest threshold for a retirement fund.[2]

This regular withdrawals of a retirement fund is very important. If we did not intend on regularly withdrawing funds, and instead only cared about pure performance, we would not need to consider stability. After all, if we only cared about the long-term outlook, we would be indifferent to any sporadic short-term fluctuations.

In this case, looking at volatility is of great importance. Let’s say you have an investment portfolio worth 25x your annual living expenses (as suggested previously). Imagine a major recession occurs, lowering your portfolio by 40% (as seen during the 2008 recession). Suddenly, your portfolio is only worth 15x your living cost, meaning that your returns will most likely be less than the amount you withdraw. If the market does not recover quick enough, your portfolio is at risk of reaching a threshold where it can no longer keep up. Instead it will continue to diminish in value over time, eventually reaching zero.

To properly consider this scenario, we will simulate purchasing a lump-sum amount of each allocation. Then, we will withdraw an annual living expense each year to see if our allocation can keep up perpetually. After a 40 year period, the final amount will be recorded. All values are also adjusted for inflation. This will be tested a number of times wich each allocation to see how likely our portfolio is still sustained, even after 40 years of constant withdrawals.

We can then check two metrics:

Sustainability: The probability that the allocation’s final valuation is greater than or equal to its starting amount.

Performance: The distribution of the allocation’s final valuation.

Of course, sustainability is the most important trait of a retirement portfolio, though we will still explore performance to see if anything interesting occurs.

Sustainability#

| Stock/Bond Allocation | Sustainable Probability |

|---|---|

| 100 / 0 | 86.93% |

| 90 / 10 | 86.93% |

| 70 / 30 | 80.39% |

| 50 / 50 | 64.05% |

| 30 / 70 | 39.87% |

Here we can see that a higher bond allocation has a negative effect on the probability that our portfolio is sustainable.

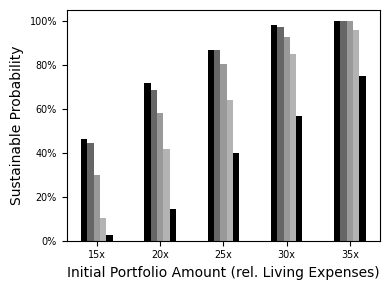

On another note, it is interesting to see that a typical 25x retirement fund still has a 13% chance of unsustainability. Perhaps a higher initial investment amount is needed? Because of this finding, I repeated the experiment with a handful of different initial portfolio sizes for two reasons:

Is the negative trend of bonds apparent across all initial investment amounts?

Is it possible to achieve a 100% sustainability rate? And if so, when?

To first explain the figure, each set of bars represents a different initial investment amount. The individual bars are the different stock/bond allocations, with the same 100, 90/10, 70/30, 50/50, and 30/70 allocations from left to right.

Here we can observe two things:

The previously discovered negative bond effect is apparent regardless of initial portfolio size.

A 100% sustainable probability is only reached at a 35x initial investment amount.

From these results, it seems that adding bonds to a retirement fund has only a negative effect on sustainability, and has no justification to be included. Additionally on another note, the commonly advised 25x initial investment amount is too low, and should instead be increased to 35x for a more robust portfolio.

Performance#

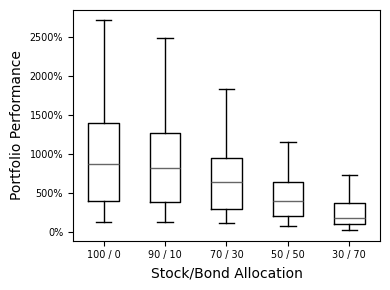

Because of the previous results, I have modified the experiment to now start with an initial 35x investment amount.

As expected, a higher bond allocation has a negative effect on our portfolio’s performance.

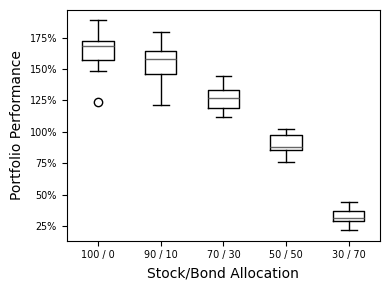

I then theorised what other use case could bonds have? Why would Vanguard’s highest risk pre-made portfolio still include bonds? Perhaps bonds would help in the absolute worst of circumstances, so I also looked at the bottom 5th percentile of results to see if any observation could be made.

Even in the bottom 5% of results, the negative effect of bonds is still visible.

I could not find any reason to include bonds at all in a portfolio.

Conclusion#

A higher bond allocation has a negative effect on both the sustainability and performance of a portfolio, and therefore has no reason to be included in a portfolio. Additionally, the threshold for a retirement fund should be increased from the commonly known 25x figure, to 35x your living expenses, as such a change would improve the probability that your portfolio is sustainable from 87% to 100% based on past performance.